Deprecated: get_currentuserinfo is deprecated since version 4.5.0! Use wp_get_current_user() instead. in /sites/dev.trca.ca/files/web/wp/wp-includes/functions.php on line 4859

In 2003, Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) initiated the West Nile Virus Surveillance and Monitoring Program as a measure of due diligence and in cooperation with our Regional Public Health partners in Durham, Peel, York and the City of Toronto.

What is West Nile Virus?

West Nile Virus primarily exists between birds and bird-biting mosquitoes. There are 57 mosquito species occurring in Ontario, of which only 13 species are capable of transmitting West Nile Virus. Humans contract West Nile Virus through the bite of an infected mosquito (i.e. vector) that has fed on an infected bird. Humans are considered dead-end hosts, meaning humans can be infected with West Nile Virus but do not spread it. For people who do become infected with West Nile Virus, the majority will have no symptoms or only mild flu-like symptoms. Severe cases of West Nile Virus including the development of meningitis and encephalitis, are extremely rare but can be fatal. More information can be obtained from your Regional Public Health units.

What are we monitoring?

TRCA monitors mosquito populations in natural wetlands and stormwater management ponds on our properties throughout the summer. The data collected are used to identify sites that contain a large number of mosquito larvae that are capable of transmitting West Nile Virus as biting adults. These sites are identified as hot spots and followed up with appropriate management actions. This program complements West Nile Virus vector source reduction activities carried out by our Regional Health partners on municipal properties. In addition to monitoring, the program includes public education and collaboration with Regional Health units. Concerns raised by citizens or staff are addressed through TRCA’s Standing Water Complaint Procedure.

What are the data telling us?

TRCA has monitored mosquito larvae in wetlands and stormwater management ponds (SWMPs) since 2003. Results have consistently shown that natural wetlands do not pose a serious West Nile virus threat. The majority of the mosquito larvae collected in wetlands have been non-vector species, those not capable of transmitting the virus. On the other hand, the vector species Culex pipiens was the most common mosquito species found in SWMPs.

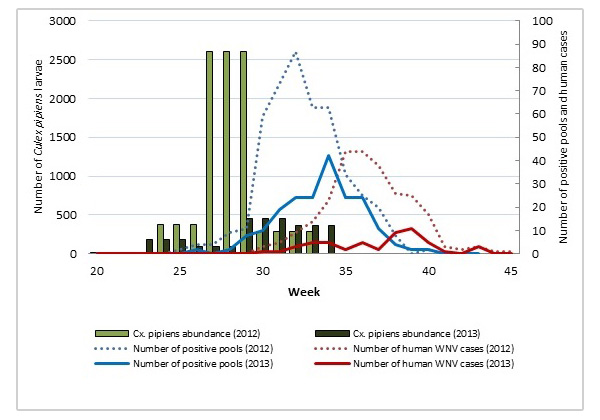

The following figure shows Culex pipiens (the most important vector West Nile virus species) abundance, the numbers of West Nile virus positive mosquito pools, and human West Nile virus cases in 2012 and 2013. This figure shows that larvae surveillance is not only used for the timely detection of West Nile virus vector species and their abundance, but is also vital in predicting adult mosquito emergence and the potential of humans contacting the virus.

More Information

- West Nile Virus Vector Larval Mosquito Annual Report, 2018

- Environmental Monitoring and Data Management Resource Library

Regional Public Health

Contact

Jessica Fang

Biologist, Aquatic Monitoring and Management

Watershed Planning and Ecosystem Science

jessica.fang@trca.ca